Media

All Heart, No Nonsense

From Golden Gloves to golden touch with kids

By Scott Wright (OFF THE TIMES HERALD STAFF)

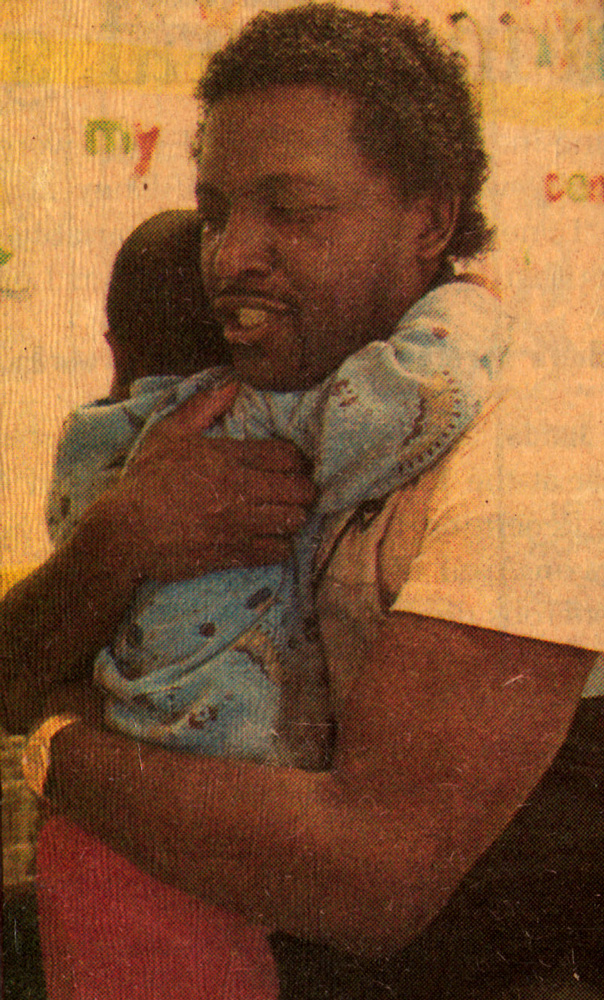

Brandon Ross gets a hug from Jordan for a job well done.

AAAAAALVIN,” squeals the little 3-year-old girl.

She darts across the playground, tugs at his pant leg and begs to be picked up. Safe in his arms, tears well up in her eyes (more for effect than because of any real pain, one would suspect).

“Jason pinched me,” she cries. She points an accusatory finger at the nervous, blond-haired boy, who has trudged over to face an uncertain punishment from the gruff-looking man who looms before him.

But Alvin Jordan has no harsh words for the boy. Instead, the former Golden Gloves champion boxer gently recites a childhood poem that tells how girls are made of “sugar and spice and all things nice” and boys of “frogs and snails and puppy dog tails.”

It’s a tale his mother once told to him after learning he had clobbered a little girl. When he’s through, both children are laughing again. They hug him and disappear back into the crowd of children outside the Turnpike Children’s Center.

Here, at the day-care center off Westmoreland Road, Jordan works with children each weekday morning. Here, surrounded by a constant swarm of small children, he is happiest, having long ago rejected a chance to become a professional boxer. For the past 20 some odd years, his career has been caring for children.

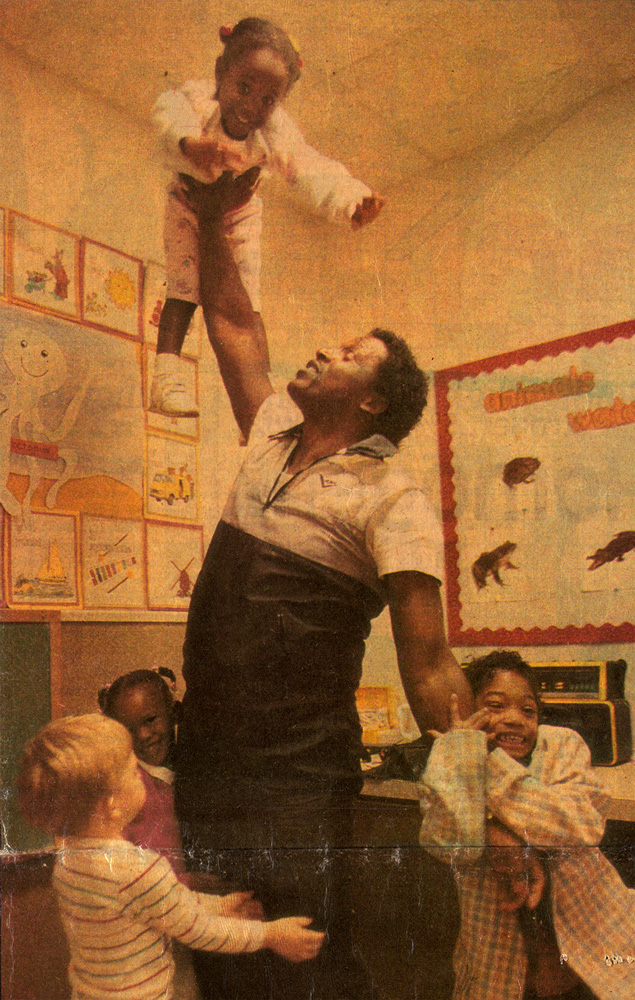

To the numerous opponents he slugged in the ring, Jordan was a tiger. To the small children he teaches at the center, he is a cuddly, king-size teddy bear. Everyone knows “Alvin.” The children, who range in age from 2 to 6, scream his name whenever he walks into a room.

They cling to him like stray socks to a shirt crackling with static as they are pulled from the dryer. They swing on his arms. They hang on his legs. And when he bends down to talk to them, almost inevitably, one climbs on his back.

“Out of all the things I could be doing, the most pleasure comes right here, working with kids,” says Jordan, 39. “Kids are special, and they should all be treated that way. I’ll never be able to give them up completely. I think I’ll always have to be around kids.”

Alvin Jordan holds Sharie Henderson high in the air, while Jesse Renna, left, Katrina Robinson and Erron Johnson await their turns.

Spud Webb’s inspiration

Spud Webb first met Jordan in 1973 at the Turnkey Boys Club in South Oak Cliff. At that time, Jordan was the club’s director, working with under-privileged youth ages 6 to 18 to keep them off the streets and out of trouble.

Jordan couldn’t help but notice Webb, a scrawny 10-year-old who lacked self-confidence, because the boy shadowed him wherever he went.

Webb, now a star point guard with the Atlanta Hawks, devotes the better part of a chapter detailing the influence Jordan had on his life in his recently released book, “Flying High” ($14.95, Harper & Row).

“I think I marveled at him so much because he was doggone little,” Jordan recalls of Webb, one of the smallest players in the National Basketball Association. “But he had the biggest heart. And he had the most courage of any kid his size I’d ever seen.”

“Since I was only 10 at the time,” Webb writes, “and my dad was gone most of the time working, much of what I learned about life and how to be a responsible kid came from Alvin…. Alvin encouraged me to make the most of my talents.”

Webb describes his childhood mentor as “a looming, serious man,” who “laid down the law with us kids and didn’t tolerate any monkey business… He also had a knack for making things fun, and lots of youngsters in the neighborhood gave up ‘hanging out with the tough guys’ to come join the Boys Club.”

But there are hints of a softer Jordan revealed in the story Webb tells of his early days in Dallas. He encouraged Webb to join the club’s football team, which went on to win a championship game against a rival Boys Club team.

“You’d think we’d won the Super Bowl,” Webb writes. “Alvin gave us a banquet and we all received trophies. Later we found out Alvin paid for much of it out of his own pocket.”

Jordan, however, waves off the praise. He insists he was simply doing his job.

“The only thing I did was be there for them when they needed me,” he says. “I feel like I played straight with all the kids. I didn’t try to trick them, just be for real with them. It always paid off in the end.”

Protecting others

Was 10 a.m. at the Turnpike Children’s Center. Jordan and Amy Torres, who teaches the class for 3- to 5-year-olds along with him, desperately try to corral an energetic bunch of kids for their morning lesson.

In this room, where everything -including the bathroom fixtures -is designed for tiny hands, Jordan seems out of place. Like a gigantic Gulliver in the land of Lilliput. He probably would squash one of the small, plastic chairs if he were to sit in one.

A fight erupts between two boys, culminating in one punching the other. Jordan takes them both aside and in a firm, but non-threatening voice, tells them to knock if off.

“What have I told you?” he asks Jesse, the boy who threw the punch. “You can’t do that and ever expect to keep friends. I’m not going to have any of that in this class. I won’t. I just won’t have it.”

His next few sentences are inaudible. But when he’s done talking, both boys are pals again.

“Firm, but fair,” says Carolyn, Jordan’s wife of three years. “I think that probably describes Alvin the best. He has this charisma with kids. They know when people care about them, and Alvin shows genuine care. They pick up on that.”

It’s been that way since Jordan was a kid growing up in a West Dallas neighborhood where crime was common and drugs easy to come by. He shrugged off the drugs. A born leader, some of the older children even followed him around.

“There were so many things that happened to us while I was growing up,” Jordan says. “Things you wouldn’t believe. We’d find guys who had been shot dead. There were fights. Domestic squabbles that led to violence. People would be stabbed and you were standing so close the blood would get on you.

“I was always wanting to protect the little kids from some of that ugliness,” he says. “I wanted to give them things they didn’t have. So I’d make wheelbarrows and stuff for us to play with out of old fruit crates, wheels and broom. handles. Junk. But most of the things I could share with the other kids were just things in my head.”

Jordan shunned sports as a child. Never liked them much. He was more interested in hanging around younger kids, writing poetry and other so-called “sissy stuff like that.” In 1966, when he was 16, the West Dallas Boys Club opened and Jordan was one of the first youths to enter its doors.

“People say the Boys Club is for disadvantaged kids, but that isn’t true,” he insists. “Because once we joined the Boys Club, we weren’t disadvantaged any more. We were lucky. They did things for us that every kid dreams of.”

It was there he began boxing. after being forced into the ring to resolve a spat with another boy. His friends on the club’s boxing team watched him fell his formidable opponent in five rounds and insisted he join. He did so reluctantly.

About the same time, Jordan also began working for the club, advancing rapidly through the ranks until he became the athletic director in 1973. He went on to oversee a Boys Club camp in Little Elm and eventually earned the directorship of the recently opened Turnkey branch in South Oak Cliff.

“I thank God for the Boys Club,” he says. “That’s where my training as a teacher and a care giver started. I don’t really have any idea why I’m good at it. I guess it’s something God just put in me.”

‘Gentle Giant’

There are those who have suggested to Jordan that men do not belong in the day-care business, especially working with small children. Jordan himself was at first reluctant to teach preschool kids after leaving the Boys Club in 1980.

“I’ll give him two weeks,” snort- ed a male maintenance worker soon after Jordan joined the staff at the First United Methodist Church’s child-development center in downtown Dallas. Jordan stayed several years before switching to the Turnpike Children’s Center where he now works.

“It seems like day care is just a field for women,” admits the father of two. “Here I am a man. So that automatically makes me an intruder. An invader. When I moved downtown, I was more or less a threat to some of the other workers, because I could do things with the kids they couldn’t.

“I was a man. I wasn’t supposed to know the things I just instinetively knew about kids,” he says. “And I was not supposed to be able to cope with the stresses of rearing children, or whatever it is they say about men helping kids.”

“He sort of comes on as macho at first sight,” says his wife, Carolyn, who met Jordan while the two worked together at the Boys Club. She has been with the non-profit organization 11 years and now holds Jordan’s former title of director at the Turnkey branch.

“But he is a very caring per- son,” she adds. “He is a great role model for the kids.”

“He really loves kids,” marvels Gwen Gilbreath, whose 9-year-old daughter Paige was in Jordan’s class at the church-run day-care center when she was 4. “And the kids love him. He can be Mr. Gruff at times, but Alvin really understands kids and treats them with respect. He never talks down to them.”

If there is one child who holds a special place in Jordan’s life, it is Paige Gilbreath. Fondness bubbles from the former boxer when he speaks of her. She still sends him a Christmas card, containing her most recent school picture, each year, he says proudly.

“There are two things I will always remember about Paige,” Jordan recalls. “If someone made

her cry, she would cry a long, long time. Two, she doesn’t like cooked carrots.”

After seeing a news segment on television that juxtaposed Jordan’s rugged boxing style with the sensitive rapport he flaunts with the kids in his classroom, Paige and her parents taped the program and showed it to everyone at the day-care center. In it, the TV reporter nicknamed Jordan the “Gentle Giant.”

“I think there is a certain gentleness in all of us,” Jordan says. “I don’t care how mean we can get. If there is a little kid around, it changes. At that moment, the gentleness comes out.”

Get in Touch with us!

Begin your adventure with a friendly greeting! Contact us now, and together we can discover endless possibilities.